Infidelity and Manic Pixie Dream Girls: A Feminist Analysis of FlCl's "Marquis de Carabas"

Magical girl syndrome, but less magical

*this is the second piece in my analysis of FlCl, the first can be found on my profile*

The third episode of FlCl, titled “Marquis de Carabas” or “マルラバ” is notably different than the other five episodes of the short series. Rather than focusing on protagonist Naota, “Marquis de Carabas” shifts the narrative by developing a side character, Eri Ninamori, in this female-centered episode. As Ninamori clashes with Haruko, the episode unknowingly pitches the two female characters against each other. While both characters share many of the same traits, Ninamori's character is unlikable to Naota—who now prefers the manic company of Haruko. Haruko’s sloppy, erratic, and controlling traits pioneer her character to be somewhat of a ‘manic pixie dream girl’, while Eri, a more serious character, is berated for her leadership. Other than this internal battle between Ninamori and Haruko, “Marquis de Carabas” continues FlCl’s female driven sexual themes, in addition to the ‘seductress’ trope. Each female character in the episode (the reoccurring Mamimi and Haruko and newcomers Eri Ninamori, her father’s mistress/secretary, and Naota’s school teacher) all portray obnoxiously negative traits that any male critic would dub as ‘hysterical’. Even with these criticisms, FlCl still twists the narrative to demonstrate female depth and emotional intelligence through each character. Keeping this in mind, it’s difficult to determine if these characters serve as mere misogynistic tropes or as satirical commentary on how women are portrayed in Japanese animation—and their limitations. FlCl’s ‘half-joking’ and absurdist traits make this question quite complicated when looking through the lenses of feminist criticism.

To chronical the plot of “Marquis de Carabas”, the episode begins with Naota’s classmate, Eri Ninamori, in the backseat of a car driven by a seductive woman applying makeup. The woman is revealed to be the secretary and extramarital affair of Ninamori's father—the mayor of Mabase. News of the Mayor’s cheating scandal strikes Mabase and Naota’s school, but Ninamori is more focused on the upcoming school play: Puss in Boots. With Ninamori playing the lead role, Naota is voted to play the cat—something he outwardly protests.

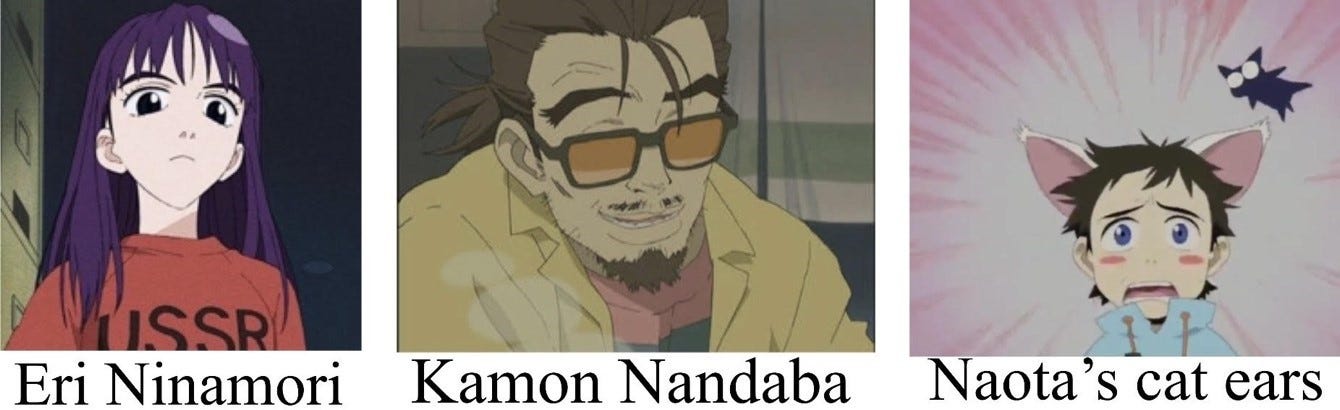

Later, Naota grows a new ‘wound’ from his head, this time in the shape of cat ears which Mamimi discovers when the two meet up after Naota skips play rehearsal. It’s also mentioned here that Mamimi’s parents are separated and that she’s been skipping school. In the afternoon, Ninamori flees from the media frenzy outside of her house and hangs out in the Mabase train station until Naota finds her. Then, Haruko appears on her Vespa and crashes it into the two kids, causing Ninamori to discover and subsequently touch Naota’s cat ears after his hat falls off.

Back at Naota’s house, his father Kamon invites Ninamori to spend the night over a meal of curry cooked by Haruko, which she accepts before complaining of stomach pains from the spicy curry and from being struck by Haruko’s Vespa earlier. Later in Naota’s bedroom, Ninamori confesses that she rigged the class vote to ensure that she would play the lead role and Naota would play the cat in the school play. The following day at school, a fight breaks out between the two kids over their production of Puss in Boots, with Ninamori revealing Naota’s cat ears to the class before they disappear from his head and reappear on hers. In the final scenes of the episode, a monster grows out of Ninamori's new cat ears which is later defeated when Haruko arrives with Canti (and with the help of spicy curry). The school play goes on, and Naota monologues that Ninamori's father didn’t face charges from his affair and that life should go back to normal for her soon.

PART ONE: Infidelity and Ninamori

In the opening scene, viewers see the secretary tell Ninamori she “handled that well” and that “the mayor was worried [she’d] be upset” (00:12) as she gazes into a hand mirror and applies lipstick. The secretary then tells Ninamori not to worry and that she “won't do anything to ruin [her] father’s reputation” (00:39). In this brief dialogue, it’s implied Ninamori had just found out that her father was having an affair, to which she replies: “It’s ok, I’m not worried—you seem like a smart secretary” and “you slept over last night, but you put on a different suit this morning” (00:46), indicating that this isn’t the first time her father had slept with a secretary—but this was the first time that the infidelity was leaked to the public.

While at first glance this scene seems like a stereotypical depiction of a seductive secretary, the conversation between her and Ninamori has a strong sense of intelligence and maturity—at least from Ninamori's character. In addition to the viewers, the secretary also notes this, saying that she is “very mature” and “very levelheaded” (00:29 & 00:39). Ninamori's efforts to be perceived as an adult mirror Naota’s, but her lines lack his typical aggression—making her an emotionally mature character that has simply been tainted by the adult world of seduction and infidelity. Still, Ninamori's lines don’t make up for the existence of the secretary character, who is arguably misogynistic in nature—reiterating the idea that women are seductresses at the workplace.

Looking at the secretary, nearly all assets of her shallow character are riddled with misogyny. Her opening scene depicts her seductively applying beauty products with close-up shots, cementing her character’s presence as inherently sexual before viewers ever see her full face. Although it’s implied that she has just told a child, Ninamori, that she is sleeping with her father, the secretary’s demeanor remains unbothered and borderline calculated as she doesn’t face Ninamori once during their entire conversation. This presents her character as someone with extremely low ethics, working in her own favor without giving any consideration to those around her. Within the narrative, these traits establish her as a sexual villain without any mention of Ninamori’s father—who arguably would have more control over the affair considering the power dynamics between men and women in addition to a workplace (especially political) environment.

Outside of the narrative, these traits put the secretary in the infamous and outdated ‘femme fatale’ trope, a seductress archetype defined by a female character’s unavoidable seduction that results in chaos through her manipulation and ulterior motives. Although everything that the viewers know about the affair would point to Ninamori’s father abusing his power, the secretary’s character design, voice acting, and personality make her seem like the one that’s in control. While the affair seems to be more than consensual, the tired presence of the ‘femme fatale’ in media promotes blaming women in negative sexual situations—whether it be an affair or sexual assault—since the trope continuously defines women as undeniably sexual and men as unable to control themselves when faced with such a woman (or character).

In addition to this, the secretary’s lack of name recognition further dehumanizes her character. While this choice shines a light onto Ninamori’s point of view (the affair is more notable to her than the people involved), it’s still rather uncomfortable when viewing through feminist perspective. The secretary exists as an enigma, someone unworthy of a name and only deemed relevant because of her promiscuous behavior and appearance. Although the mystery surrounding the secretary benefits Ninamori’s development in symbolizing her thoughts on the affair, this restates the secretary’s existence as an unbenevolent and greedy seductress—which, even for the purpose of character development, reiterates this trope as valid.

In contrast to the secretary, Ninamori's character is incredibly well developed within the short twenty-three-minute episode. FlCl isn’t afraid to portray strong female characters within a wide range of personality—Haruko's chaotic nature, Mamimi’s delusional depression, and finally Eri Ninamori’s uptight ambition. In a feminist praise of FlCl, Ninamori isn’t defined by her structured personality, but these traits open her psyche and unlock a much deeper character. Rather than existing exclusively to foil Haruko, Ninamori's development justifies her action with her troubling backstory. To compare, the 2017 anime Death Note fails miserably at developing its female characters, as noted in the female lead, Misa Amane. Misa exists only as a love interest to the main character, and her hyperbolically annoying personality and voice acting are never explained or reasoned with—making her come off as the infamous ‘bimbo’ stereotype. In just one episode, FlCl was able to subvert this typical depiction of women by giving Ninamori a complicated history—something Death Note (which had forty-million-dollar budget) couldn’t do in all its thirty-seven episodes. In other words, Ninamori's traits alone don’t make her character worthy of feminist praise, but when partnered with her developed backstory, it’s easy to view her very existence as a positive one towards female depiction in media.

While Ninamori's existance subverts the expectation of female characters in anime, the circumstances surrounding her are somewhat...comme ci, comme ça. On one hand, the affair between the secretary and Ninamori’s father exposes the reality behind political power dynamics, but on the other hand reinstates female tropism in media. Ninamori's father is placed in a traditionally patriarchal role as the Mayor of Mabase and uses his influence to begin an affair with his secretary, a story that seems to be repeated in real life regardless of job title. Portraying this abuse of power in media—particularly in Japanese media, shifts the paradigm in interesting ways to ultimately be political commentary on power dynamics and sex. Still, “Marquis de Carabas” doesn’t villainize the mayor or even show him on screen—but makes frequent references to the secretary and her conniving, manipulative traits. Whether or not FlCl did this intentionally to showcase how women often face the brute of negative press in sex scandals (Monica Lewinsky, Marilyn Monroe and Stormi Daniels, just to name a few) or if they subconsciously fed into this pattern, is a mystery.

Looking inside the narrative for gender-based analysis, one could say that Ninamori's character is the byproduct of toiling with misogyny in daily life. While much of her internal struggle could be more significant to Japanese viewers considering that ‘women’s roles’ are more rigidly upheld in Japan, Ninamori's character is still one that would resonate with female Western audiences. Ninamori is seemingly forced into her ‘it is what it is’ attitude as a way of coping with the affair. Her father’s frequent infidelity and contrasting job title puts Ninamori into a pickle, considering she’s dealing with complex family issues but must put on a brave face to avoid further harassment—regardless of how she’s actually feeling. While Ninamori's emotional distance is troubling to watch, it’s not surprising when looking at the rest of the female cast. FlCl’s other female characters are pitied and mocked (like Mamimi in “Firestarter”) when expressing emotion, an issue prevalent in real society. Here, Ninamori is not only coping with her father’s infidelity but additionally is forced into suppression to avoid ridicule.

Diving back into the narrative, after the secretary drops Ninamori off at school, Naota and two of his male classmates look over a zine, notably published by “a store that still sells Crystal Pepsi” (03:36) (we’ll be coming back to this later). However, their homeroom teacher sees that the zine is about the mayor’s affair and bans all outside media “of low taste”, telling the kids through a megaphone that “it’s impolite to Ninamori-san!” and they should “think about Ninamori-san's feelings!” (04:05 and 04:08). This catches Ninamori’s attention as she innocently mutters “Huh?” (4:11), looking up through wide eyes as her classmate's stare at her. Although she previously showed a tough exterior with the secretary, her reaction to her classmates knowing about the affair makes her appear small and defeated—proving that underneath her cold attitude lies a confused and isolated child.

Looking at Ninamori unrelated to the affair, her character shares many of the same traits as Haruko, although she serves as her foil. While it’s notable to admit that the two characters have extremely contrasting personalities, their ‘bossy’ nature and need for initiative mirror one another. Still, Ninamori’s uptight traits make her controlling nature less attractive and thus annoying in the eyes of Naota. On the opposite side of the coin, “Marquis de Carabas” is the first episode of FlCl that shows Naota’s attraction to Haruko and enjoyment in being around her. Although both Ninamori and Haruko dictate the events of Naota’s life (in both Puss in Boots and his reoccurring head wounds), he clearly prefers the company of Haruko since her cool demeanor is now attractive to him. In later scenes of the episode when Haruko and Ninamori spend time at Naota’s house, he isolates Ninamori by shooting down her ideas and showing off Haruko like she’s his new pet.

While Naota’s discomfort with Ninamori spending the night at his house is obvious, his father, Kamon, is visibly more enthuisiastic for her to sleep over. Still, Kamon’s excitement stems from a place of selfishness. Going back into the narrative, after school Ninamori locates the store that “still sells Crystal Pepsi” (3:36), a detail she overheard from her classmates when they were looking at the zine. Upon going inside, Ninamori realizes that the storefront is the bottom half of Naota’s house, run by his father. As images of the zine play on screen, Ninamori lurks in the background, realizing that it was Kamon who had published them in the first place. Not knowing that Ninamori is the mayor’s daughter, he attempts to sell her a copy before she goes home to the media frenzy that awaits her. Later, when she returns to Naota’s house to spend the night, Kamon realizes his discrepancy and that Haruko hit Ninamori with her Vespa. He changes his demeanor and eagerly asks her to spend the night, not to comfort the young girl—but to avoid getting in trouble with the mayor. This is just another example of how Ninamori’s life has been tainted by the men around her but continues to suppress her emotion by repeatedly saying “It’s no big deal”.

On the other hand, Ninamori is unlikable to Naota because she doesn’t add anything new into his life and is thus deemed a useless burden. When considering that Haruko’s character is supposed to be a metaphor for giving him an erection, Naota’s avoidance of Ninamori is troubling suggesting that since she doesn’t do anything for him sexually, he has no need for her. “Marquis de Carabas” pitches Haruko and Ninamori up against one another by deeming leadership qualities and initiate as ‘bad’ on Ninamori, and ‘good’ on Haruko. Ultimately, Ninamori’s character is significantly more realistic to that of a real person, someone whose less-than-desirable actions mirror their troubled background, but is still rejected for not being more animated. On the other hand, Haruko serves as a character that swoops into Naota’s life and promises him excitement and change regardless of her unrealistic traits and chaotic nature. Through a feminist lense, this comparison would claim that men’s view of women exclusively revolves around their chances of having sex with them or being sexually stimulated by them. Looking at both Haruko, Ninamori, and the secretary, FlCl makes it clear that desirable women are mere enigmas, but whether this choice was made as feminist commentary or is misogynistic in nature remains unknown.

PART TWO: The Manic Pixie Dream Girl and Haruko

In 2007, writer Nathan Rabin coined the term ‘manic pixie dream girl’ in an essay reviewing the movie Elizabethtown on AV Club. Rabin defines this character trope as one that “exists solely in the fevered imaginations of sensitive writer-directors to teach broodingly soulful young men to embrace life and it’s infinite mysteries and adventures” and later saying that “the manic pixie dream girl is an all-or-nothing proposition”. While FlCl predates the phrase ‘manic pixie dream girl’, Haruko’s character mirrors its traits as she springs into Naota’s mundane life and breathes an enigmatic neon light into the ordinary town of Mabase—without Naota ever having to lift a finger. Within the narrative, Haruko’s story begins in the first episode, “Fooly Cooly”. As Naota and Mamimi stand on top of a local bridge, Naota becomes fed up with Mamimi’s antics. Just as he’s about to express his frustrations with her, Haruko swoops in and whisks him away from his tedious and boring world—showing him how exciting life can be. The manic pixie dream girl is a character that appears and suddenly everything is better. In the world of FlCl, all Naota had to do to grow was simply wait around until Haruko appeared, who forces change upon him whether he likes it, or not.

As a result, Naota’s frustrations with Haruko eventually fade as he accepts his new life and ultimately falls in love with her. While Naota has lived in Mabase his whole life, Haruko—a newcomer from outer space—changes his entire worldview. His once mundane environment turns into one of pleasure and anticipation as Noata fights off alien robots, monsters, and embraces the whimsical adventure that life has in store for him. Still, he ignores the obvious signs of Haruko’s selfish nature—she exclusively works in her own self-interest and send Naota into battles that could cost him his life—and yet, in “Marquis de Carabas” and the remainder of the series he couldn’t be more thrilled to prove himself to her by any means necessary. Haruko’s character lives exclusively for herself and this freedom brings great suffering into the lives around her. Still, Haruko isn’t a manic pixie dream girl because of these qualities—she's a manic pixie dream girl because Naota’s fetishization of her forces her to be. Naota doesn’t care about Haruko’s motivations or even her personhood, he only cares about how she can benefit his life—which, in a way, makes these two characters exactly the same.

Looking outside of the narrative, YouTuber ProfessorViral notes that the manic pixie dream girl label “started as a convenience—a way to call out filmmakers for utilizing female characters as simple tools for development for a male lead for making them no more than a simple fantasy.” (00:54). While Rabin’s article originally served as a cinema criticism, the label has fallen prey to misuse in recent years and real people have been thrown under its weight, which resulted in Rabin’s 2014 article, “I’m Sorry for Coining the Phrase ‘Manic Pixie Dream Girl’”. Characters with these qualities like Haruko (Summer from 500 Days of Summer or Ramona Flowers from Scott Pilgrim Vs. The World) have falsely been dubbed as valuable romantic partners, which they are not. The purpose of a manic pixie dream girl in media is to transform disgruntled male characters into hopeful ones but disappearing entirely, so when people dub real women as this trope—it's almost always out of selfish interests. To reiterate, the manic pixie dream girl doesn’t exist because of the woman herself, but rather because of the way men use her as a tool for their own growth.

Another asset of the manic pixie dream girl is their male relatability—or, for lack of a better term, being ‘not like other girls’. Haruko is messy and carefree—her bed in Naota’s room is covered in garbage and she takes interest in typically male activities: riding and fixing up her Vespa, playing the guitar, and playing baseball in a later episode—oh, and assaulting people. In short, Haruko isn’t afraid of getting her hands dirty. While not all manic pixie dream girls share these exact same attributes, they all reject femininity—which is for some reason, attractive to heterosexual men.

Still, it would be deceitful to not admit the strength of Haruko’s character. Overall other characters in FlCl, Haruko is arguably the strongest—her very presence shakes the entire narrative and is responsible for the plot itself. While Haruko is by no means a weak or underdeveloped character, her traits are still entangled in tropism and ultimately serve as fetishization. Looking at other similar characters who suffered the same fate (Lucy Kushinada in Cyberpunk: Edge Runners, Misato Katsuragi in Neon Genesis Evangelion, and Mai Sakurajima in Rascal Does Not Dream of Bunny Girl Senpai—spoiler, he does) marks the misogyny within the trope. Rather than inspiring female audiences, one can speculate that these characters are typically more significant to the male gaze. The manic pixie dream girl reinforces the idea that a ‘cool’ girl can transform the lives of those around her without them having to put in any effort. In addition to this, this character is almost never allowed to have a sense of personhood or emotions—always remaining energetic and hopeful.

Some iterations of the manic pixie dream girl have played against this fallacy by giving the narrative a realistic ending—typically with her either leaving (500 Days of Summer) or exposing the negative side of being unapologetically carefree (Jane Margolis’ death in Breaking Bad). Still, using this trope—even for the purpose of satire—once again reinstates its creation as valid. Considering the constant misusage and misunderstanding of the manic pixie dream girl (men claiming they want to date her, or women claiming they are her), there seems to be limited ethical concepts of this trope that aren’t still riddled with misogyny. With that being said, it’s necessary to jump a few episodes forward to fully analyze Haruko and FlCl’s tropism.

In the final two episodes of the series, “Brittle Bullet” and FLCLimax”, Haruko’s character breaks from the manic pixie dream girl trope by showing her cruel nature. Without giving too much away, Haruko reveals that she’s been using Naota to get closer to a legendary space pirate. Each robot/monster that emerges from his head and subsequent battle draws in this mysterious figure—who has the power to conquer universes. Haruko’s goal is ultimately to serve herself as she later attempts to steal this power in the final episode. Haruko is by no means a good person, but she recognizes the trope she’s in—using it for her advantage. Still, her selfishness reflects human nature and was easily predicted by Naota if he wasn’t so enthralled by her. Haruko isn’t a bad person because of this selfish desire—but because of Naota’s delusional fetishization of her.

While this strays away from the typical use of a manic pixie dream girl, the recent satirical iterations of this character (as mentioned above) use this same negative ending, which, in a misunderstanding of the trope, have redefined it to resemble the ‘femme fatale’. Haruko’s selfishness plays into this satire—but this doesn’t redeem her character. In a way, this only makes it worse as she’s portrayed as manipulative and conniving. When looking back to the metaphor of Haruko giving Naota an erection through symbolism, this has some rather...uncomfortable insinuations. While they seem worlds apart, Haruko and the secretary aren’t so different in the end—both using their sexuality for their own prowess, a tired and obnoxious portrayal of women.

So where does this leave Ninamori? I’m not sure—and neither were the writers at Gainax, as she appears as only a background character in the rest of the series.